Introduction

There are two schools of thought about performing computations in your database: people who think it's great, and people who are wrong. This is not to say that the world of functions, stored procedures, generated or computed columns, and triggers is all sunshine and roses! These tools are far from foolproof, and ill-considered implementations can perform poorly, traumatize their maintainers, and more, which goes some way toward explaining the existence of controversy.

But databases are, by definition, very good at processing and manipulating information, and most of them make that same control and power available to their users (SQLite and MS Access to a lesser degree). External data processing programs start on the back foot having to pull information out of the database, often across a network, before they can do anything. And where database programs can take full advantage of native set operations, indexing, temporary tables, and other fruits of half a century of database evolution, external programs of any complexity tend to involve some level of wheel-reinvention. So why not put the database to work?

Find out how to use functions with Prisma in the Prisma documentation.

Here's why you might not want to program your database!

- Database functionality has a tendency to become invisible -- triggers especially. This weakness scales approximately with the size of teams and/or applications interacting with the database, as fewer people remember or are aware of the in-database programming. Documentation helps, but only so much.

- SQL is a language purpose-built for manipulating data sets. It isn't especially good at things that aren't manipulating data sets, and it's less good the more complicated those other things get.

- RDBMS capabilities and SQL dialects differ. Simple generated columns are widely supported, but porting more complex database logic to other stores takes time and effort at minimum.

- Database schema upgrades are usually more fraught than application upgrades. Rapidly-changing logic is best maintained elsewhere, although it can be worth another look once things stabilize.

- Managing database programs isn't as straightforward as one might hope. Many schema migration tools do little or nothing for organization, leading to sprawling diffs and onerous code reviews (sqitch's dependency graphs and reworking of individual objects make it a notable exception, and migra seeks to sidestep the problem entirely). In testing, frameworks like pgTAP and utPLSQL improve on black-box integration tests but also represent an extra support and maintenance commitment.

- With an established external codebase, any structural change tends to be both effort-intensive and risky.

On the other hand, for those tasks to which it's suited, SQL offers speed, concision, durability, and the opportunity to "canonize" automated workflows. Data modeling is more than pinning entities down like insects to cardboard, and the distinction between data in motion and data at rest is a tricky one. Rest is really slower motion in finer grade; information is always flowing from here to there, and database programmability is a powerful tool for managing and directing those flows.

Some database engines split the difference between SQL and other programming languages by accommodating those other programming languages as well. SQL Server supports functions written in any .NET Framework language; Oracle has Java stored procedures; PostgreSQL allows extensions with C and is user-programmable in Python, Perl, and Tcl, with plugins adding shell scripts, R, JavaScript, and more. Rounding out the usual suspects, it's SQL or nothing for MySQL and MariaDB, MS Access is only programmable in VBA, and SQLite is not user-programmable at all.

Using non-SQL languages is an option if SQL is inadequate for some task or if you want to reuse other code, but it won't get you around the other issues that make database programming a many-edged sword. If anything, resorting to these complicates deployment and interoperability further. Caveat scriptor: let the writer beware.

Functions vs procedures

As with other aspects of implementing the SQL standard, the exact details vary a bit from RDBMS to RDBMS. In general:

- Functions cannot control transactions.

- Functions return values; procedures may modify parameters designated

OUTorINOUTwhich can then be read in the calling context, but never return a result (SQL Server excepted). - Functions are invoked from within SQL statements to perform some work on records being retrieved or stored, while procedures stand alone.

More specifically, MySQL also disallows recursion and some additional SQL statements in functions. SQL Server prohibits functions from modifying data, executing dynamic SQL, and handling errors. PostgreSQL didn't separate stored procedures from functions at all until 2017 with version 11, so Postgres functions can do almost everything procedures can, barring transaction control.

So, which to use when? Functions are best suited to logic which applies record by record as data are stored and retrieved. More complex workflows which are invoked by themselves and move data around internally are better as procedures.

Defaults and generation

Even simple computations can make trouble if they're performed often enough or if multiple competing implementations exist. Operations on values in a single row -- think converting between metric and imperial units, multiplying a rate by hours worked for invoice subtotals, calculating the area of a geographic polygon -- can be declared in a table definition to address one or the other problem:

Most RDBMSs offer a choice between "stored" and "virtual" generated columns. In the former case, the value is calculated and stored when the row is inserted or updated. This is the only option with PostgreSQL, as of version 12, and MS Access. Virtual generated columns are computed when queried as in views, so they don't take up space but will be recalculated more often. Both sorts are tightly constrained: values can't depend on information outside the row they belong to, they can't be updated, and individual RDBMSs can have still more specific limitations. PostgreSQL, for instance, forbids partitioning a table on a generated column.

Generated columns are a specialized tool. More often, all that's needed is a default in case a value isn't supplied on insert. Functions like now() show up frequently as column defaults, but most databases allow custom as well as built-in functions (except MySQL, where only current_timestamp may be a default value).

Let's take the rather dry but simple example of a lot number in the format YYYYXXX, where the first four digits represent the current year and the latter three an incrementing counter: the first lot produced this year is 2020001, the second 2020002, and so on. There's no default type or built-in function which generates a value like this, but a user-defined function can number each lot

If you're using Prisma, our documentation covers the equivalent method of defining default values for your fields. Prisma Client also supports aggregation, which allows you to perform count, average, and similar operations on data without separate storage.

Referencing data in functions

The sequence approach above has one important weakness (and lot_counter will still have the same value it did on December 31. There's more than one way to track how many lots have been created in a year, though, and by querying lots itself the next_lot_number function can guarantee a correct value after the year rolls over.

Workflows

Even a single-statement function has a crucial advantage over external code: execution never leaves the safety of the database's ACID guarantees. Compare next_lot_number above to the possibilities of a client application or even a manual process, executing

Multi-statement stored programs open up an immense space of possibilities, since SQL includes all the tools you need to write procedural code, from exception handling to savepoints (it's even Turing complete with window functions and common table expressions!). Entire data-processing workflows can be performed in the database, minimizing exposure to other areas of the system and eliminating time-consuming roundtrips between the database and other domains.

So much of software architecture in general is about managing and isolating complexity, preventing it from spilling across the boundaries between subsystems. If some more or less complicated workflow involves pulling data into an application backend, script, or cron job, digesting and adding to it, and storing the result -- it's time to ask what really necessitates venturing outside the database.

As mentioned above, this is an area where differences between RDBMS flavors and SQL dialects come to the fore. A function or procedure developed for one database probably won't run on another without changes, whether that's substituting SQL Server's TOP for a standard LIMIT clause or completely reworking how temporary state is stored in an enterprise Oracle to PostgreSQL migration. Canonizing your workflows in SQL also commits you to your current platform and dialect more thoroughly than almost any other choice you can make.

Computations in queries

So far we've looked at using functions to store and modify data, whether bound to table definitions or managing multi-table workflows. In one sense, that's the more powerful use to which they can be put, but functions have a place in data retrieval as well. Many tools you may already use in your queries are implemented as functions, from standard built-ins like count to extensions such as Postgres' jsonb_build_object, PostGIS' ST_SnapToGrid, and more. Of course, since those are more tightly integrated with the database itself they're mostly written in languages other than SQL (e.g. C in the case of PostgreSQL and PostGIS).

If you often find yourself (or think you might find yourself) needing to retrieve data and then perform some operation on each record before it's really ready, consider transforming them on the way out of the database instead! Projecting some number of business days out from a date? Generating a diff between two JSONB fields? Practically any calculation that depends only on the information you're querying can be done in SQL. And what's done in the database -- as long as it's accessed consistently -- is canonical as far as anything built on top of the database is concerned.

It has to be said: if you're working with an application backend, its data access toolkit may limit how much mileage you get out of augmenting query results with functions. Most such libraries can execute arbitrary SQL, but those which generate common SQL statements based on model classes may or may not allow customizing query SELECT lists. Generated columns or views can be an answer here.

Triggers and consequences

Functions and procedures are contentious enough among database designers and users, but things really take off with triggers. A trigger defines an automatic action, usually a procedure (SQLite allows only a single statement), to be executed before, after, or instead of another action.

The initiating action is generally an insert, update, or delete to a table, and the trigger procedure can usually be set to execute either for each record or for the statement as a whole. SQL Server also allows triggers on updatable views, mostly as a way to enforce more detailed security measures; and it, PostgreSQL, and Oracle all offer some form of event or

A common low-risk usage for triggers is as an extra-powerful constraint preventing invalid data from being stored. In all major relational databases, only primary and foreign keys and UNIQUE constraints can evaluate information outside the candidate record. It's not possible to declare in a table definition that, for example, only two lots may be created in a month -- and the simplest database-and-code solution is vulnerable to a similar race condition as the count-then-set approach to lot_number above. To enforce any other constraint which involves the entire table, or other tables, you need a

Once you start executing lots itself may be the final operation of a trigger initiated by an insert into orders, with no human user or application backend empowered to write to lots directly. Or as items are added to a lot, a trigger there might handle updating current_quantity, and start some other process when it reaches the target_quantity.

Triggers and functions can run at the access level of their definer (in PostgreSQL, a SECURITY DEFINER declaration next to a function's LANGUAGE), which gives otherwise limited users the power to initiate wider-ranging processes -- and makes validating and testing those processes all the more important.

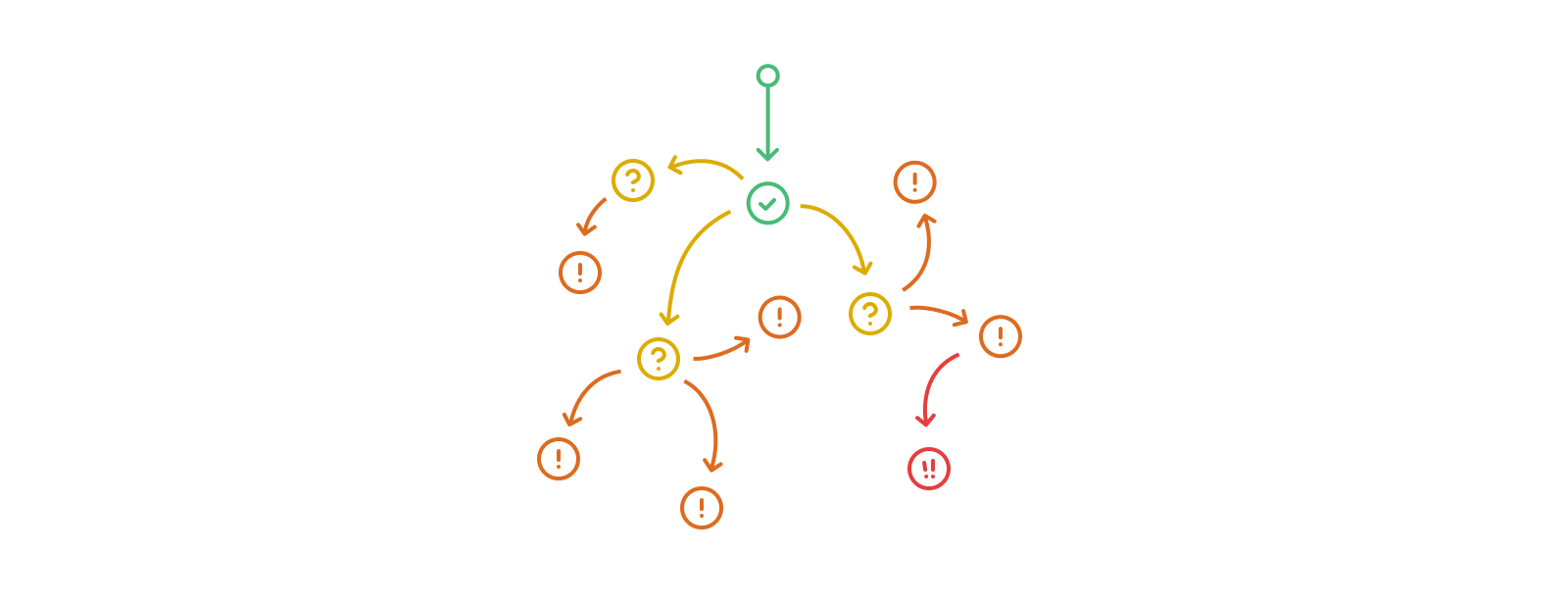

The trigger-action-trigger-action call stack can become arbitrarily long, although true recursion in the form of modifying the same tables or records multiple times in any such flow is illegal on some platforms and more generally a bad idea in almost all circumstances. Trigger nesting rapidly outstrips our ability to comprehend its extent and effects. Databases making heavy use of nested triggers begin to drift from the realm of the complicated toward that of the complex, becoming difficult or impossible to analyze, debug, and predict.

In Prisma Client, you can achieve similar results with TypeScript at the client level instead of SQL by using middleware. Middleware allows you to perform an action before and after every query (e.g., turn a delete query into a "soft" delete which toggles a record's visibility instead).

Practical programmability

Computations in the database aren't just faster and more concisely expressed: they eliminate ambiguity and set standards. The examples above free database users from having to calculate lot numbers themselves, or from worries about accidentally creating more lots than they can handle. Application developers in particular have often been trained to think of databases as "dumb storage", providing structure and persistence only, and can thus find themselves -- or worse, not realize that they are -- clumsily articulating outside the database what they could do more effectively in SQL.

Programmability is an unjustly overlooked feature of relational databases. There exist reasons to avoid it and more to limit its use, but functions, procedures, and triggers are all powerful tools for limiting the complexity your data model imposes on the systems in which it's embedded.

If you want to learn more about what data modeling means in the context of Prisma, visit our conceptual page on data modeling.

You can also learn about the specific data model component of a Prisma schema in the data model section of the Prisma documentation.

FAQ

A stored procedure is a prepared piece of SQL code that you can save and reference to be used when needed.

It is particularly useful for SQL queries that you are writing often because you can just call the stored procedure and execute it rather than re-writing the query.

The basic syntax can look something like this:

You can then call the procedure using an execute statement:

Database functions are a set of SQL statements that perform a specific task. They are efficient ways to packages lines of SQL code that you can reference rather than rewriting the actual SQL.

Database functions are a good way to promote reusability in your code. Functions and procedures both allow for better reusability in code, but they have some differences that are good to know when modelling your database.

A generated column is a database column that is computed based on a predefined expression or from other columns.

It is a way of storing data without actually sending it through the INSERT or UPDATE clause in SQL.

Depending on your choice of database provider, you will notice default databases that come with your instance.

Most RDBMs ship default databases that store required information by the server. These can include metadata tables, other system information, or templates.

A database trigger is procedural code that is automatically executed in response to certain events or criteria on a table or database.