Data modeling

Know your problem space

Introduction

Some aspects of data modeling get subjective. Actually, it's fair to say that most aspects of data modeling are subjective, despite the very mathematical foundations of it all. Any question of how to represent information has many answers, and it isn't always clear which one best applies in context. Before getting into implementation details you should seek to understand that context and the requirements as well as you possibly can. This takes time, and other people's time, and lots of questions. Research and interviews are just as important for database design as they are for user experience design: incomplete, too-detailed, invasive, or poorly structured data can make life at least as painful for users and subjects as for a system's maintainers! Even if you're being handed requirements and told to execute, you are most likely the first person to think all the way through the problem and its possible consequences.

The crux of the data modeling problem is defining useful entities and identifying whether and how they relate to one another in a web or graph of connections. These entities represent classes of physical objects or intangible concepts -- and more than a few things in between, such as locations, shipments, or assignments. But the representations occupying this semiotic space aren't bound by physical laws, and there is not necessarily a strict one-to-one correspondence between signifier and signified. A single entity might represent an aspect shared by many of the concepts you're working with, or even an entire subsystem; alternatively, what seems like a singular concept might be more useful or more manageable broken up into many.

Any entity by itself can only mean so much. The Zulu proverb "a person is a person through other persons" is not untrue for abstract representations either. Data models rarely represent singular categories of isolated facts; more often they represent systems, and the relations and interactions of even a few components are as important to an accurate and useful representation of the system as are the components themselves.

Subjectivity makes it impossible to answer these questions in the abstract. This is an exercise to think through, and to investigate actively by asking people with a stake in the data you collect. Even then, the answers you draw up initially will be provisional at best; rare is the data model which survives unchanged until release.

What is important enough to qualify as an entity?

"What categories do we really care about?" is a question so obvious it can escape the asking, even when you're about to set your assumptions in stone. Defining the subjects and objects of your system is the first thing to think about no matter what database you're using. It's also relevant to the choice of data store: if you care about massive quantities of instrument readings or other straightforward facts you'll read much more often than you update, for example, that should point you towards columnar databases like Cassandra or HBase.

Relational databases are complicated. When speaking of systems, the complicated must be distinguished from the complex. Complex systems include neural networks, economies, languages, life itself: each component interacts with many others based on limited contextual information, the system as a whole interacts with its environment, histories and behaviors emerge.

Complicated systems, meanwhile, are merely made up of a lot of individual parts, each acting and being acted upon with the rhythm of a clock or an engine. It's possible to encode histories in and define behaviors for a database, but doing so is a strictly top-down exercise; no seemingly-emergent characteristic of a data model is ever anything more than a deterministic bug. Elements of a data model interact with others, but always the same others in the same ways. And some elements are to representation in a database as a screen door is to a submarine, adding at best only an extra point of mechanical failure.

Which connections among entities matter?

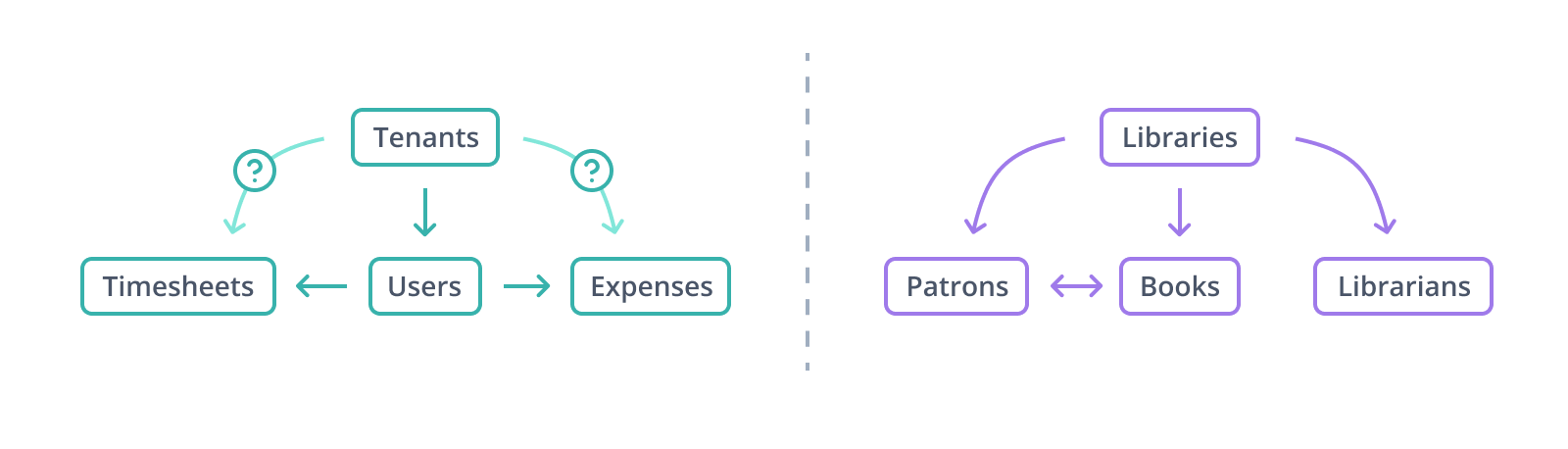

There are two ways of designing a data model where multiple userbases and their data are stored in the same tables. We'll return to the broader problem of multitenancy later, but there's a specific choice with a shared-schema model that exemplifies some major concerns in modeling: should every record include a tenant_id value, or just those with a direct, meaningful connection to a tenant?

Conceptually, it's not very difficult to identify to which tenant a row belongs as long as foreign key constraints are enforced. One JOINs from table to table back towards tenants following the relationships, and then whichever join products include the tenant_id value you're looking for belong to that tenant. Managing the SQL can get pretty wretched as the schema evolves further, though, and with enough data in the system performance can start to be a concern. That doesn't mean managing extra tenant_id columns in more distant tables is automatically worth it, but it doesn't take a lot to make that a reasonable decision either.

Entities and relationships constitute a directed graph of nodes and edges. "Directed" here means that an edge is a one-way connection. A record with a tenant_id value implies both the existence of the tenants table and of a specific record therein (with proper foreign key constraints set up, it guarantees rather than implies!); however, a record from tenants itself implies nothing about what other data might belong to it.

Every additional node or edge complicates the graph, which in turn means maintaining and improving the data model further will require more effort. However, this complexity is a local as well as a global concern. Sets of entities can be connected in tangles of important-enough relationships, which are challenging both to manage and to use. These subsystems can often be shielded to some extent by mechanisms like views or table inheritance as in PostgreSQL, with a net effect not unlike the Façade pattern in object-oriented software development.

How do organizational units interact?

Any element of your model -- be it an entity, a relationship, or a subgraph comprising multiple entities and relationships -- may represent a part of the organization you're designing for or a locus of interaction between such units. Inventories connect manufacturing with logistics, or logistics with sales. Expense records link finance and HR, and HR to departments throughout a company. Some actors may interact with a model chiefly through a handful of entities at the edge; this can present challenges if they have little insight into the deeper workings of the system, or opportunities to improve the overall functioning of your organization by giving them more visibility and contact with the rest.

Few observations have held up like Conway's Law: organizations are condemned to reproduce their communication structures in their system designs, and databases are no exception. Some data modeling problems are, in whole or in part, really communications issues for which databases may be scant help.

How much detail?

It's also useful to flip the first two questions around: what will the data model's users miss if we outright ignore this possible entity or that relationship? Most elements you've initially identified as important, of course, are so. But some may not be as crucial as they seemed at first blush, and omitting or simplifying them can improve the overall functioning and maintainability of the model.

The question of importance has more answers than "yes" and "no". You might not need to represent some aspect of your problem space as an entity in its own right, but still care about generic, easier-to-manage facts like presence or quantity. In manufacturing, a part number is the key to a wealth of information about calibration, process history, subcomponents, capacities, tolerances, and more, with different characteristics mattering for different part types. In warehousing, part numbers become SKUs (from "stock keeping unit") and the crucial details are a lot simpler: how many, in what color, weighing how much, and where are they?

Some information too is useful, but already has its own internal structure which is less than convenient to transform into entities and relationships. Hierarchies, hypertext documents, bills of materials, even transient "working copies" of entity-relationship subgraphs elsewhere in the database; these or the information they contain can be represented relationally, but unless there are important relationships crossing the boundary between external and internal structure, it's likely not worth the effort of breaking them open. If this kind of information is your primary concern, specialized databases may be appropriate, like (for hierarchical documents) CouchDB or MongoDB. If they're exceptions to an otherwise relational model, data types such as JSON and XML can help avoid splitting your model across two or more databases. Not only is each additional data store more work to maintain and coordinate, referential integrity, the guarantee that information a relationship is predicated upon won't up and vanish, only holds inside a single database.

What subgraphs, aggregates, and statistics are useful?

Querying a relational database takes time. How much time specifically depends on a wide variety of factors: physical properties of the host computer like disk speed and CPU power, operational capabilities of the RDBMS in question such as caching and optimization, and finally the composition of the query itself. Your data models must accommodate the limits set by the first two classes, but one of the chief determinants of their success will be how well they anticipate the problems of the third.

The number of relationships spanned is one of the most important aspects of query composition both for performance and for maintainability. A high JOIN count doesn't necessarily mean unacceptable performance, especially if the entities being joined are small or well-indexed, but even in the best case each one adds to the cognitive burden on query authors. It should be as straightforward as possible for you, backend developers, and other database users to assemble commonly-needed result sets.

Databases provide some tools to help accomplish this. Views encapsulate commonly-used subgraphs and computations on them, which can help shield complexity from users and applications. Centralizing your second-order representations in the database also ensures there's a single canonical representation of, say, a purchase order with all attendant information, or common statistics for warehouses. Ordinary views do nothing for performance, since they're stored queries which get integrated into a running statement. Most relational databases, however, support "materialized" views (MySQL and MariaDB being the notable exceptions). These persist their data to disk like tables, making retrieval much faster, but that data then becomes outdated and has to be refreshed.

The last resort here is denormalization: storing an entity's data or useful aggregates such as counts or totals inline as properties of a different entity. We'll delve more deeply into normal forms in a future chapter, but suffice to say this is not a step to take lightly. Still, if assembling the data you need is prohibitively time-consuming, abandoning higher tiers of normalization can be worth the additional management effort. If you need to go to extremes here, it's time to think about columnar databases again.

What shouldn't be stored?

You aren't responsible for information you don't have. There's a whole industry built around securing data, but no security measure is infallible. The easiest way to avoid a very sticky class of problem is not to collect data which could cause you that sort of problem. Do note that this extends beyond databases, though; sensitive information can show up in logs, reports, source control, and other systems.

The single most sensitive class of information with the most ramifications, bar none, concerns people. Information about people is necessarily political, and modeling a system in which humans participate both reflects and reinforces the politics of the modeler. Who enters or is entered into the system, in what capacities, with which characteristics assumed important or unimportant, visible to whom: politics, every bit of it. We have only barely begun to see the effects of cavalier or invasive treatment of personal data. More and more people's information is constantly being funneled into data models, and too often these models have not been developed with commensurate care. In more than a few cases, they've been designed expressly to exploit that information.

Personally identifiable information, or PII, indicates to whom other data is relevant. Without PII, a random medical record is a history in a vacuum. Somebody somewhere, known only by a number, had these childhood vaccinations, presented with pneumonia here, with a minor skin cancer there, with a substance dependency at one point, with the flu a couple times, with bipolar disorder. Attach that medical record number to a name and address and suddenly you -- or anyone who can see it -- know a lot more about a specific person's life than they may intend or want others to know. The consequences of collecting more data than we successfully protect range, for those whose data it is, from brief unpleasant conversations all the way to job loss, identity theft, blackmail, and various hate crimes.

When it comes to medical records, many countries have stringent laws governing access and disclosure, and for good cause. Information in most other contexts isn't under as strict legal controls, if any, and that means you're responsible for working out how closely you need to safeguard those names and addresses, birthdates, biometrics, mothers' maiden names, and government-assigned identity values like passport or taxpayer ID numbers. PII can pop up in places you don't expect it as well, as happened in 2004 when AOL released what they thought were anonymized search logs to the public. Worse, even non-identifying facts in sufficient quantity become identifying: how many other people have the same city of residence, gender, job title, phone model, and favorite restaurant as you? What other things might be associated with that combination of facts?

Another variety of sensitive information allows you to act on behalf of someone else. Social media or other web credentials, bank routing and account information, credit card numbers are all given to you in trust. In some cases, especially dealing with payments, third-party services exist which take this burden of trust from you. Use them unless you have a very good reason to take it on yourself.

What's going to happen next?

Data models are not static. Requirements evolve; businesses pivot; external sources of information appear, change, and disappear. This doesn't happen at the same spirited pace set by application development, but happen it does, big changes, little tweaks, and everything in between. Careful design will help keep the balance towards slower and more minor changes, but there's never any guarantee against needing to perform major surgery on a data model at some point, and even some seemingly-minor changes can present unforeseen difficulties in deployment. Until PostgreSQL 11, for example, adding a new column with a non-null default value required a rewrite of every record in the table -- not much fun with millions of rows!

The present is more important than the future. If your model is not useful now, you likely won't get the chance to see it become useful later. Forces of natural or unnatural selection are always at work, though, and databases which cannot adapt to these pressures perish. We'll address planning for future possibilities in more detail later on, but even knowing that corners exist into which you can paint yourself can help you avoid that fate.

If you want to learn more about what data modeling means in the context of Prisma, visit our conceptual page on data modeling.

You can also learn about the specific data model component of a Prisma schema in the data model section of the Prisma documentation.